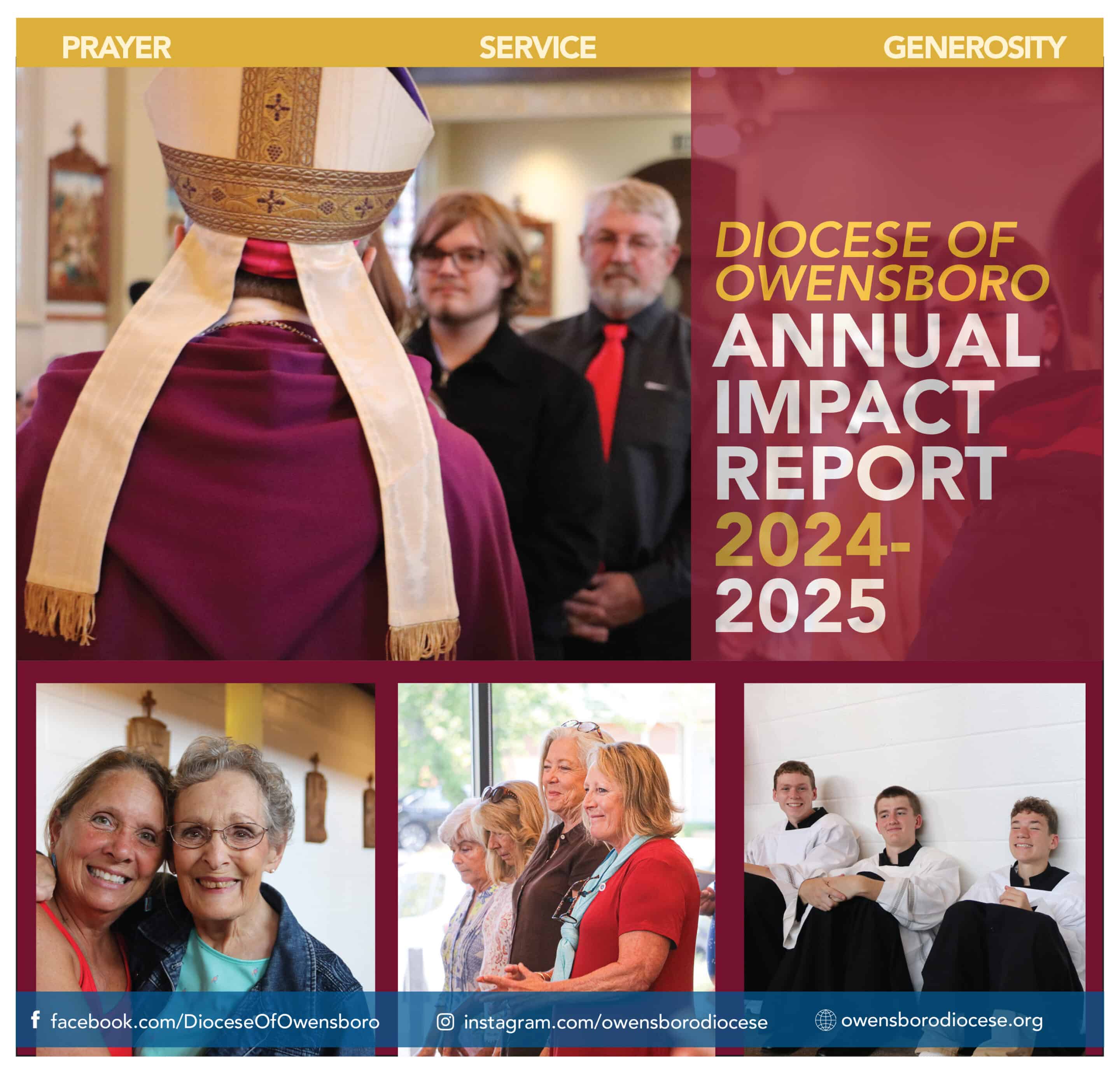

Susana Solorza, mother of Susy Solorza, prays in Capilla de San José (Chapel of St. Joseph) at Rancho El Pino, Chihuahua, Mexico, around 1993. This chapel is located on the same ranch where Susy Solorza’s great-grandfather and family would hide Padre Maldonado in their house. COURTESY OF SOLORZA FAMILY

‘The seeds he planted are still blooming’

Priest’s martyrdom inspires family’s faith to this day

BY ELIZABETH WONG BARNSTEAD, THE WESTERN KENTUCKY CATHOLIC

On Feb. 10, 1937 – Ash Wednesday – a priest named Padre Pedro de Jesús Maldonado was attacked by henchmen of the Mexican government in yet another instance of the religious persecution of Christians in Mexico at that time.

He was severely beaten and left for dead after the henchmen mockingly made him eat several Hosts which had fallen out of a pyx he was carrying (actually fulfilling the priest’s last wish to receive Jesus before dying).

Local women petitioned for the 44-year-old priest to be taken to the hospital, where he died from severe cerebral damage the following day.

On May 25, 2000, Pope St. John Paul II canonized “Padre Maldonado” as he is commonly known – confirming what many people already believed: this priest was a living saint.

Susy Solorza, a teacher at Holy Name of Jesus Catholic School in Henderson, is one of those people, and for good reason. Her great-grandfather and other family members were among the Catholics who routinely hid Padre Maldonado from the authorities.

“In my family we call him Padre Maldonado or ‘El Padre’ – ‘the priest,’” she said in a Jan. 19 interview with The Western Kentucky Catholic.

Faith of your children

Solorza said both her paternal grandmother and her maternal grandfather were baptized by Padre Maldonado, who “dressed as a rancher, going from ranch to ranch” in disguise so that he could celebrate Mass in people’s homes.

When government officials came by to look for the priest, Solorza’s great-grandfather would hide Padre Maldonado in a secret place in their house.

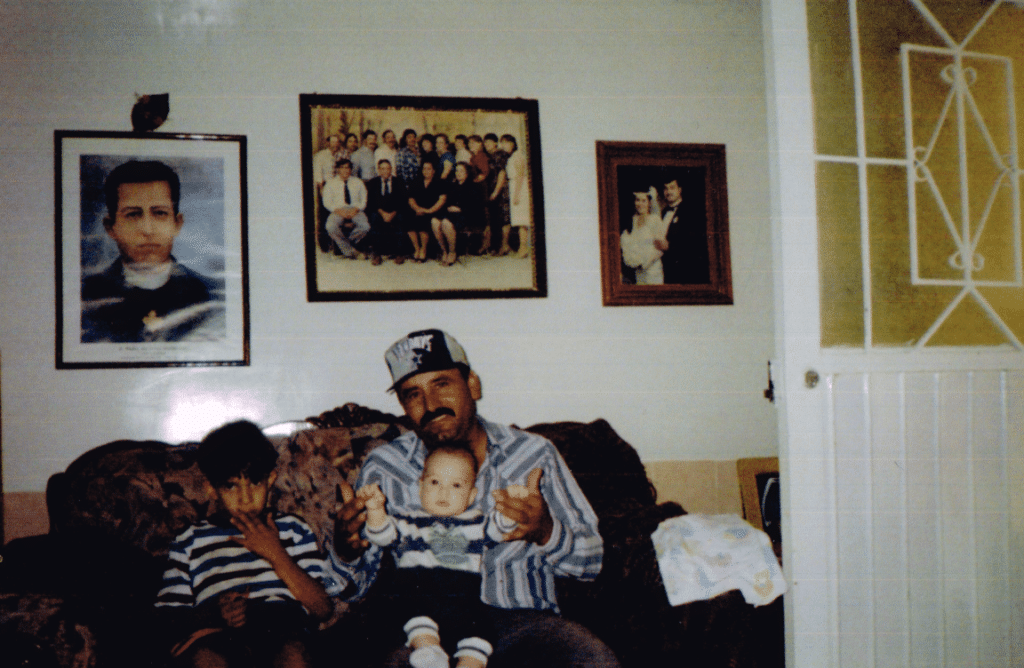

Solorza said relics of his cassocks have been kept in her extended family, and she and many of her relatives have pictures of Padre Maldonado in their homes.

“His face has always been familiar, kind of like a family member,” she said. “Kind of like a grandfather… the majority of the people he served felt that way.”

Solorza, who was born in El Paso, Texas, said Padre Maldonado also served in El Paso as he ministered all over the region. Her family members who resided in those days in Chihuahua, Mexico (not far from El Paso), had a ranch with a chapel dedicated to St. Joseph – where Padre Maldonado would celebrate Mass.

Before Solorza’s immediate family moved from Texas to Kentucky, they would join extended family for a yearly visit and Mass at the little chapel in honor of Padre Maldonado. As they drove out to the chapel, Solorza and her siblings were retold the story of his martyrdom.

“My mom always told us ‘the seeds he planted are still blooming,’” said Solorza.

She is grateful to have been raised in a faith-filled environment, especially crediting the faith of her paternal and maternal grandmothers who dedicated their lives to “service in the Church.”

Solorza shared a story which has been passed down through the generations.

“One of my great-grandfathers was out walking and the soldiers stopped him and asked him where to find Padre Maldonado,” she said. He refused to tell them.

The soldiers told him: “We may not take your faith, but we’ll take the faith of your children and descendants.”

That account is one of the reasons why Solorza and her four siblings find it crucial to hold onto their Catholic faith, which their ancestors fought so hard to maintain.

Solorza and her husband, John Shelman, live this out by intentionally teaching the faith to their two young sons, Santiago and Luca.

Susy Solorza’s older brother, Bayardo Solorza, sits beside their uncle Eugenio, who is holding their younger brother, José, in their grandparents’ living room in Anahuac, Chihuahua, around 1997. A picture of Padre Maldonado hangs alongside pictures of other family members, as he has always been considered a part of the family. COURTESY OF SOLORZA FAMILY

Domestic church

Solorza said she reflected on the Mexican Catholics’ commitment to the faith during the March 2020 shutdown when the COVID-19 pandemic first struck the United States, and businesses and churches were closed for several months.

This included a temporary suspension of public worship, which meant no one could receive the Eucharist.

“Whether I was five years old in Mexico or 20 years old in college, I always had the opportunity to find a Catholic church where I could receive the Eucharist,” said Solorza. “Not once, in all my life, had being present at Mass been out of my reach. This pandemic brought my family’s past experience of not being able to celebrate Mass to life for me.”

The first Sunday they were able to return to Mass, Solorza cried as they walked into Holy Name of Jesus Parish and were welcomed by the entire parish staff.

“To this day, as my husband and I wrestle with two toddlers during Mass, those moments where I am most frustrated, I think back to the beauty of sitting in this pew, sharing this time, singing these songs with my family and our fellow parishioners,” she said.

She said the martyrdom of Padre Maldonado, and the faith of her great-grandparents, are the foundation on which her own parents built their domestic church.

“Today, John and I draw from our own families and their journeys of faith to build this chaotic, bilingual, multicultural domestic church of our own,” she said.

Did you know?

Hiding priests was common among the faithful during the 1926-1937 religious persecutions of Christians in Mexico. St. Toribio Romo, another Mexican priest who was ultimately martyred by the authorities, was sometimes hidden by the family of the great-grandmother of Dcn. Chris Gutiérrez, director of the Diocese of Owensboro’s Office of Hispanic/Latino Ministry.

Listen & learn

Listen to José Solorza tell the story of his faith journey through the intercession of San Pedro de Jesús Maldonado on the “Finding Faith” podcast: https://apple.co/34EsGtY.

Originally printed in the March 2022 issue of The Western Kentucky Catholic.